Perspective

Global Surveys Challenge Assumptions on Public Opinion of SRM

Chad M. Baum and colleagues from the GENIE project summarise findings from several public perception studies based on extensive surveys and focus groups in 30 countries. They find that the public is more supportive of sunlight reflection methods (SRM) than many assume, and that support is greater in the Global South, among other insights.

Photo: Chung Sung-Jun / Getty Images

In discussions about SRM, a handful of assumptions about public opinion are often taken for granted. Some of these well-worn tropes have gone largely unexamined – until recently. Specifically, that:

- SRM is inherently controversial, reflected by broad, intrinsic public opposition;

- Opposition is most prevalent in the Global South, particularly if the activities are to be located there;

- And there is broad support for a global ban or moratorium on SRM.

These claims about public attitudes seem to have emerged from assumptions made in expert or policy debates, or to have derived from well-publicized events. For example, the campaign led by the Sámi Council against the SCoPEx field experiment in northern Sweden1 or the announcement by the Mexican government that it was taking steps to restrict geoengineering after the unauthorized trial by Make Sunsets.

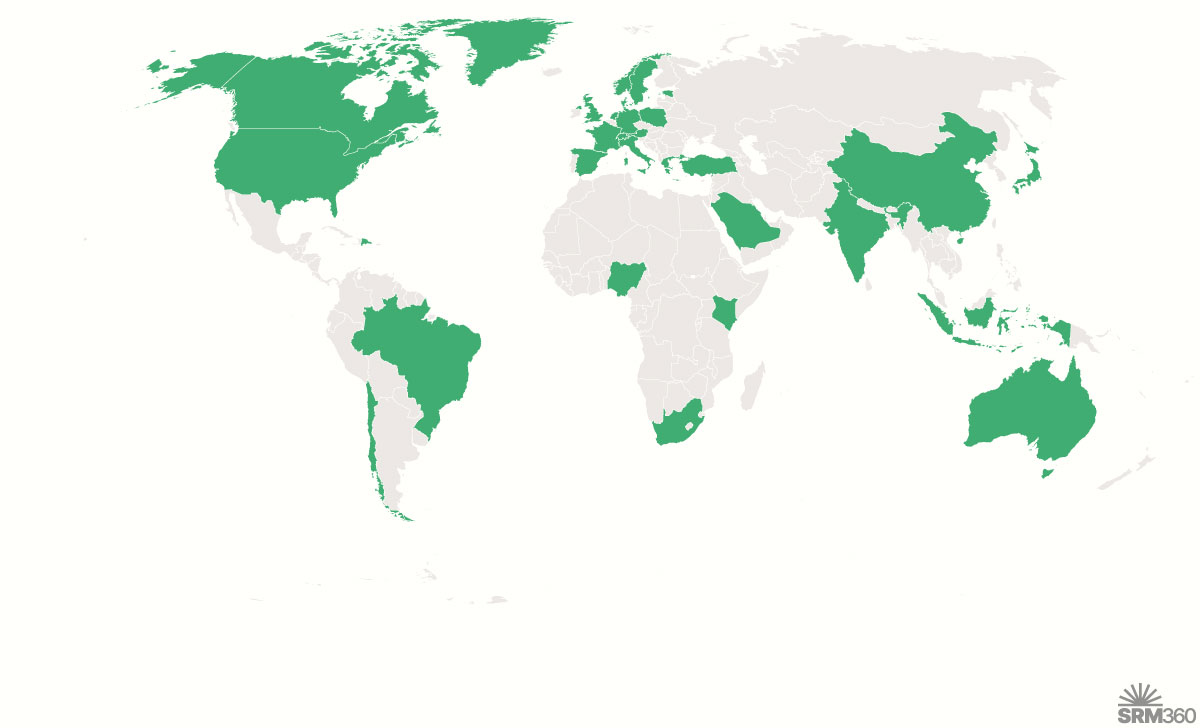

But new evidence strongly challenges some conventional assumptions about public attitudes. Over the last three years, as part of a team of researchers at Aarhus University in Denmark working on the EU-funded GENIE and ELEVATE projects, we have published 10 articles examining public perceptions of SRM. This research draws on a globally distributed set of nationally representative surveys in 30 countries (with 30,284 participants in total), and 44 focus groups in 22 countries (one urban, one rural each; with 323 participants in total).2

This research yielded important insights into public perceptions of SRM, which we summarize here. It is our hope that these insights will shape ongoing discussions and debates around SRM, and that our work makes clear the need for inclusive and deep engagement with the general public.

The countries surveyed: Australia, Austria, Brazil, Canada, Chile, China, Denmark, Dominican Republic, Estonia, France, Germany, Greece, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Kenya, Netherlands, Nigeria, Norway, Poland, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, UK, USA.

The countries surveyed: Australia, Austria, Brazil, Canada, Chile, China, Denmark, Dominican Republic, Estonia, France, Germany, Greece, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Kenya, Netherlands, Nigeria, Norway, Poland, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, UK, USA.

Public awareness remains limited

Awareness and understanding of SRM remains low around the world. Typically, 75–80% of those surveyed say that they either know very little or nothing at all about SRM.3,4

Public engagement is an important part of governing SRM research, but this lack of awareness limits the ability of the public to take a proactive approach in this discussion. It also poses the risk of interested actors attempting to speak up on behalf of publics,5 to the potential neglect of their perspectives and concerns.

More of the public support SRM than reject it

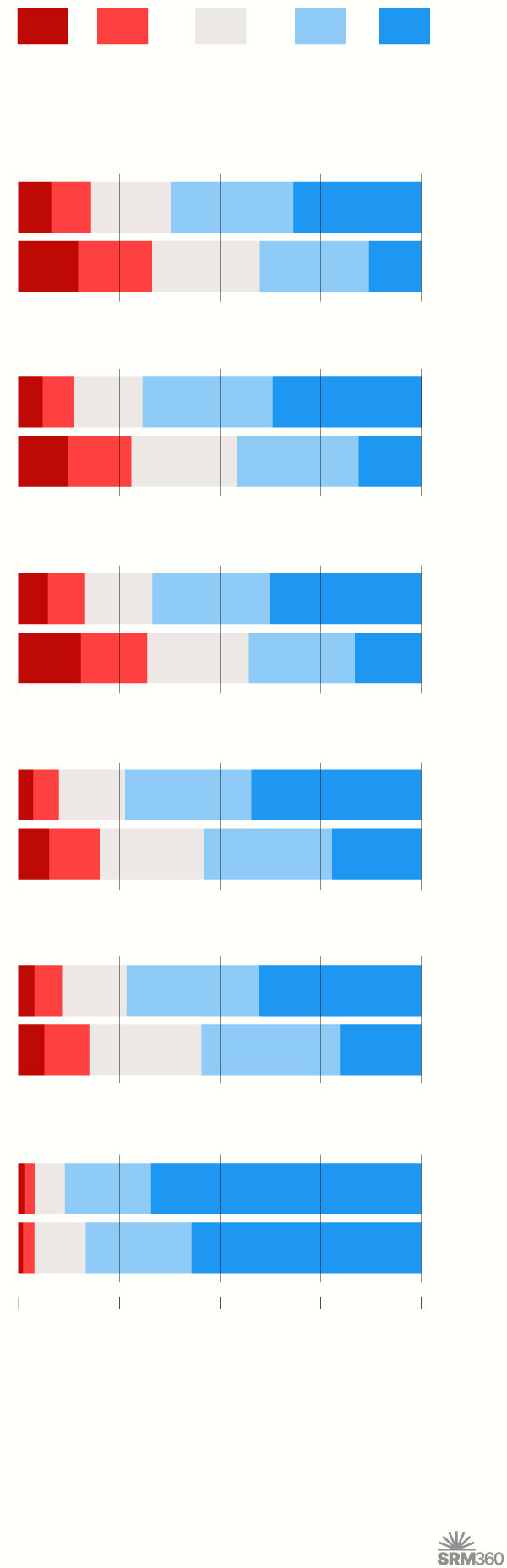

Contrary to common belief, there is little evidence that global publics broadly reject the idea of SRM. Those who “strictly reject” the broad deployment of stratospheric aerosol injection (SAI), for instance, amounted to 12% across the world.6 In contrast, almost 20% of the participants “fully support” the deployment of SAI. The proportion that supports small-scale field trials is higher still, at 57% of those surveyed.

We found that support for SRM was driven by several motivating factors. These included how much one is worried about climate change and how negatively impacted one expects to be now and in the future.2 We also found that the level of trust in certain actors matters, specifically the firms and companies in the climate technology sector and/or national governments.6 Lastly, the belief that science and technology will eventually find a solution to climate change is also crucial.3,6

Nevertheless, the support for SRM technologies was much lower than for other climate interventions. Ecosystems-based carbon dioxide removal (CDR) options received the most support, with novel engineered CDR approaches in the middle.

We found that SRM approaches, and SAI in particular, were the most divisive of the options considered. Even if only a relatively small segment of the population outright rejected these options, vocal minorities can have an outsized influence on how discussions evolve.

Support for types of climate intervention

Results from surveys in 30 countries, asking “How much do you support the broader deployment of each of the technologies to limit the effects of climate change?”

Fully reject

Somewhat reject

Neither reject nor support

Somewhat support

Fully support

income level:

Stratospheric aerosol injection

middle

High

Marine cloud brightening

middle

High

Space-based geoengineering

middle

High

Direct air capture with carbon storage

middle

High

Bioenergy with carbon capture and storage

middle

High

Afforestation and reforestation

middle

High

0

25

50

75

100%

Notes: A survey of 30,284 respondents across 30 countries; income groups are based on the World Bank’s latest classification of countries.

Source: Brutschin et al. (2024), Environmental Research Letters

Fully reject

Neither reject nor support

Somewhat reject

Somewhat support

Fully support

Stratospheric aerosol injection

income level:

Middle income

8%

10

20

30

32%

High income

15%

18

27

27

13%

Marine cloud brightening

Middle income

6%

8

17

32

37%

High income

12%

16

26

30

15%

Space-based geoengineering

Middle income

7%

9

17

29

37%

High income

16%

16

25

26

16%

Direct air capture with carbon storage

Middle income

4%

6

16

31

42%

High income

8%

13

26

32

22%

Bioenergy with carbon capture and storage

Middle income

4%

7

16

33

40%

High income

6%

11

28

34

20%

Afforestation and reforestation

Middle income

2%

3

7

21

67%

High income

1%

3

13

26

57%

Notes: A survey of 30,284 respondents across 30 countries; income groups are based on the World Bank’s latest classification of countries.

Source: Brutschin et al. (2024), Environmental Research Letters

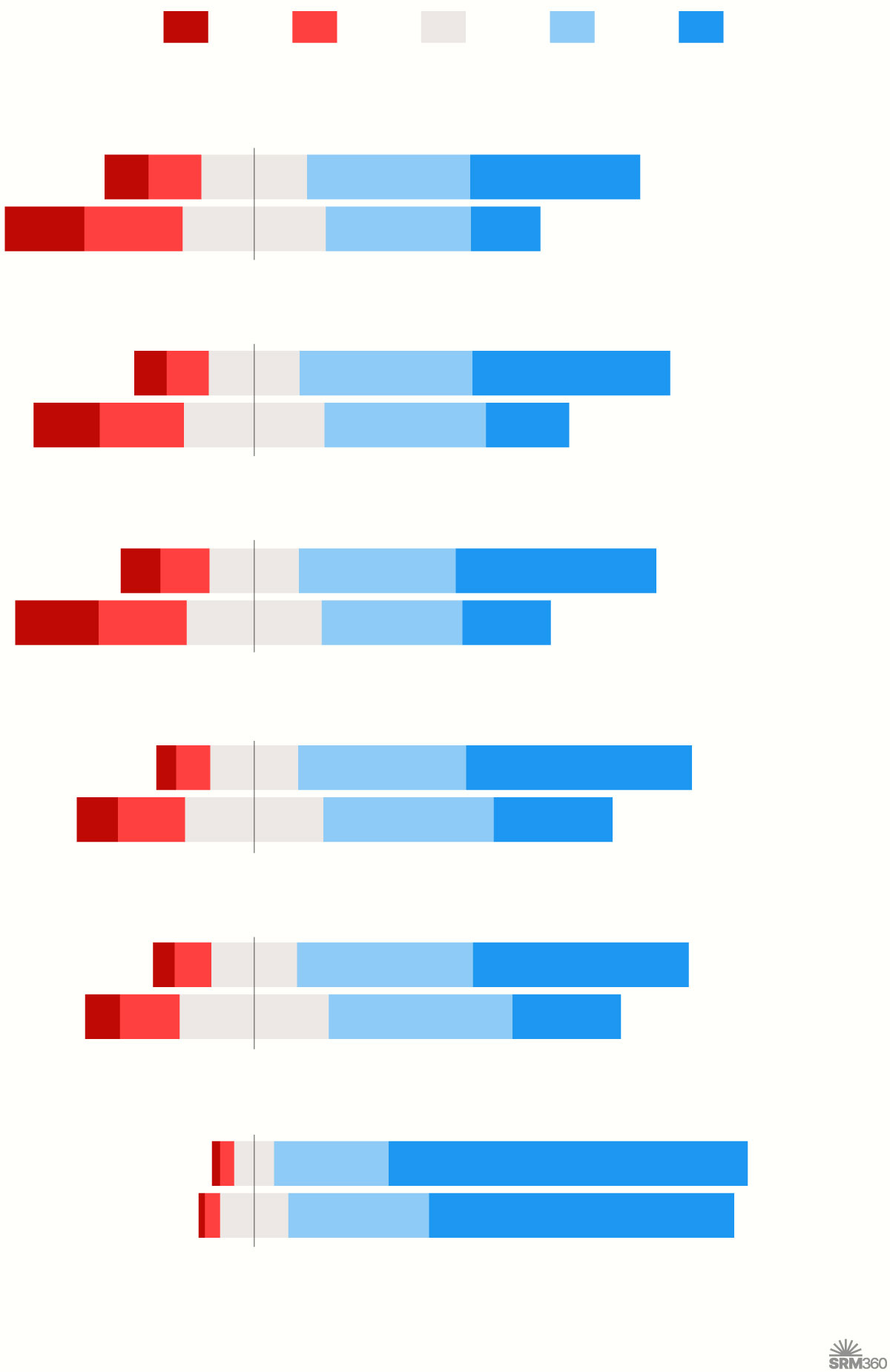

Global South publics appear more supportive and positive towards SRM

According to our surveys, those in the Global South were more supportive and positive about the benefits of SRM than those in the Global North.3,7 These differences were more pronounced for SRM than CDR.

Publics in the Global South were not unconcerned about the risks of SRM; however, their concerns differed from publics in the Global North. In the Global North there was greater concern about unintended side effects and threats to humans and nature, while in the Global South there were greater concerns about disproportionate burdens imposed on poor countries and the potential for SRM to undermine emissions cuts.

Focus groups made clear that those in the Global South simultaneously expressed greater hope and deeper concerns regarding SRM.8 Their concerns focused on inadequate levels of funding for taking climate action, the failure of the Global North to make sufficient cuts to emissions, and the prospect of SRM giving rise to geopolitical conflict.

Agreement (+) and disagreement (−) with statements about benefits and risks of SRM

| Benefits | ||

| Can be done safely in a controlled fashion | ||

| Cost-efficient and cheaper than cutting use of fossil fuels | ||

| Environmentally friendly | ||

| Can be counted on in the long term | ||

| Risks | ||

| Leads to unintended side effects | ||

| Would distribute risks unequally between rich and poor countries | ||

| Threat to humans and nature | ||

| Would decrease the motivation to reduce CO2 emissions |

+3 = strongly agree; −3 = strongly disagree (re-coded from initial scale of 1 to 7, with 4 = Neither agree nor disagree). All differences between the Global South and Global North are statistically significant (from Figure 3, Baum et al. 2024)3.

Greater support for information and engagement than bans

The possibility of a moratorium or non-use agreement9 on SRM has been attracting considerable interest in expert and policy circles. However, support for an international ban is muted among global publics. Around one-third of participants in both the Global North and Global South supported an international ban on SRM – the lowest level of support shown for any surveyed SRM policy. In contrast, information and engagement campaigns with the public as well as national-level support for research and development received much greater support from most participants, particularly in the Global South.

A subsequent survey undertaken after the announcement that Make Sunsets had released test ballons in Mexico further emphasized this pattern.7 Participants from Mexico were actually more supportive of SRM activities being done in Mexico rather than in the UK. They were also more generally supportive of developing and deploying SRM than those in the UK or US. Those in Mexico deemed national-level regulation and oversight to be very important – but again there was little support for an international ban or moratorium.

Towards broad, deep, and fundamentally inclusive dialogue

By engaging with publics in 30 countries across the world, we were able to better understand how they actually think about SRM, challenging some common assumptions. Instead of a public broadly opposed to SRM research or deployment, we found one that is probably best described as open but cautious towards SRM.

Importantly, we found that support for SRM was greater in the Global South than in the Global North. The fact that most previous studies of public perceptions addressed only the Global North is likely why misconceptions around the views in the Global South are so common.

We also found a degree of polarization around SRM, with some strongly against and others strongly supportive. It is worth stressing that most participants had not heard about SRM. Views on this topic are quite likely to shift substantially if and when it emerges more clearly into the public consciousness.

Something we heard repeatedly in focus groups was a demand for more engagement10 – the public wants to be involved in this debate. They also generally trust experts and wish to become informed about the topic.11 However, they are deeply skeptical about the prospects for multilateral governance and whether they will be allowed to play a meaningful role in discussions and decisions.8

Meeting these demands and engaging with these concerns will be a significant challenge, but one which the SRM community should not shy away from. This is the moment to prioritize conversation and deliberation that is broad, deep, and fundamentally inclusive11 – not to shut it down prematurely or seek to bypass public engagement in favor of a narrow, elite-dominated consensus.

The views expressed by Perspective writers and News Reaction contributors are their own and are not necessarily endorsed by SRM360. We aim to present ideas from diverse viewpoints in these pieces to further support informed discussion of SRM (solar geoengineering).

Endnotes

- Oksanen AA. (2023). Dimming the midnight sun? Implications of the Sámi Council’s intervention against the SCoPEx project. Frontiers in Climate. 5:994193. https://doi.org/10.3389/fclim.2023.994193

- Fritz L, Baum CM, Brutschin E, et al. (2024). Climate beliefs, climate technologies and transformation pathways: Contextualizing public perceptions in 22 countries. Global Environmental Change. 87:102880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2024.102880

- Baum CM, Fritz L, Low S, Sovacool BK. (2024). Public perceptions and support of climate intervention technologies across the Global North and Global South. Nature Communications. 15(1):2060. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-46341-5

- Contzen N, Perlaviciute G, Steg L, et al. (2024). Public opinion about solar radiation management: A cross-cultural study in 20 countries around the world. Climatic Change. 177(4):65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-024-03708-3

- Táíwò OO, Talati S. (2022). Who are the engineers? Solar geoengineering research and justice. Global environmental politics. 22(1):12-8. https://doi.org/10.1162/glep_a_00620

- Brutschin E, Baum CM, Fritz L, et al. (2024). Drivers and attitudes of public support for technological solutions to climate change in 30 countries. Environmental Research Letters. 19(11):114098. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ad7c67

- Baum CM, Fritz L, Low S, Sovacool BK. (2024). Like diamonds in the sky? Public perceptions, governance, and information framing of solar geoengineering activities in Mexico, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Environmental Politics. 33(5):868-95. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2023.2301262

- Low S, Fritz L, Baum CM, Sovacool BK. (2024). Public perceptions on solar geoengineering from focus groups in 22 countries. Communications Earth & Environment. 5(1):352. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01518-0

- Biermann F, Oomen J, Gupta A, et al. (2022). Solar geoengineering: The case for an international non‐use agreement. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change. 13(3):e754. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.754

- Fritz L, Baum CM, Low S, Sovacool BK. (2024). Public engagement for inclusive and sustainable governance of climate interventions. Nature Communications. 15(1):4168. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-48510-y

- Fritz L, Losi L, Baum CM, et al. (2025). Between inflated expectations and inherent distrust: How publics see the role of experts in governing climate intervention technologies. Environmental Science & Policy. 164:104005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2025.104005