Perspective

Given the Political Landscape, Arctic SRM Is Neither Feasible nor Desirable

Nikolaj Kornbech argues that the fraught political landscape in the Arctic makes the region poorly suited for the deployment of sunlight reflection methods (SRM), and that the promotion of Arctic SRM could make matters worse.

While solar radiation modification (SRM) is mostly imagined as a global intervention, the Arctic has been singled out as a region for deploying SRM with a more limited scope. But in an increasingly strategic and conflictual Arctic political climate, SRM would likely destabilise things even further. Arctic SRM is therefore unlikely to succeed, and it is imprudent to promote it if it distracts from the urgent need for mitigation and adaptation.

Many different ideas for SRM have been explored by scientists and entrepreneurs as ways to stabilise or lower temperatures in the Arctic, even as most research has been restricted to modelling studies. Ideas include making marine clouds brighter,1 covering surfaces with reflective materials,2 and thickening sea ice using wind-powered water pumps.3 Not all such techniques are likely to be effective or desirable from a technical perspective,4–6 and in January 2025 the Arctic Ice Project – which had proposed spreading small silica-based beads to increase the reflectivity of ice – was stopped, in part due to concerns about the risk of toxic effects on the Arctic food chain.

In addition to such technical uncertainties, there is, however, an additional element of political uncertainty which is too often overlooked. In fact, those working on Arctic SRM projects tend to believe that “Arctic interventions pose less of a governance challenge than global climate interventions”, as Daniel Bodansky and Hugh Hunt argue.7 They highlight the existence of the Arctic Council as an effective institution for getting countries to agree on Arctic SRM, while others have emphasised the small number of countries that would need to come to an agreement.8 But recent research, including recent work by Olaf Corry, Duncan McLaren, and myself, raises serious doubts about the Arctic as a politically conducive region for SRM.9

In our paper,10 we analysed literature on Arctic SRM, looking into the assumptions researchers and entrepreneurs had about Arctic politics. We also asked how the Arctic climate was understood as a problem that could potentially be addressed via SRM. We then compared and contrasted their views with those expressed in recent policy documents of Arctic states.11

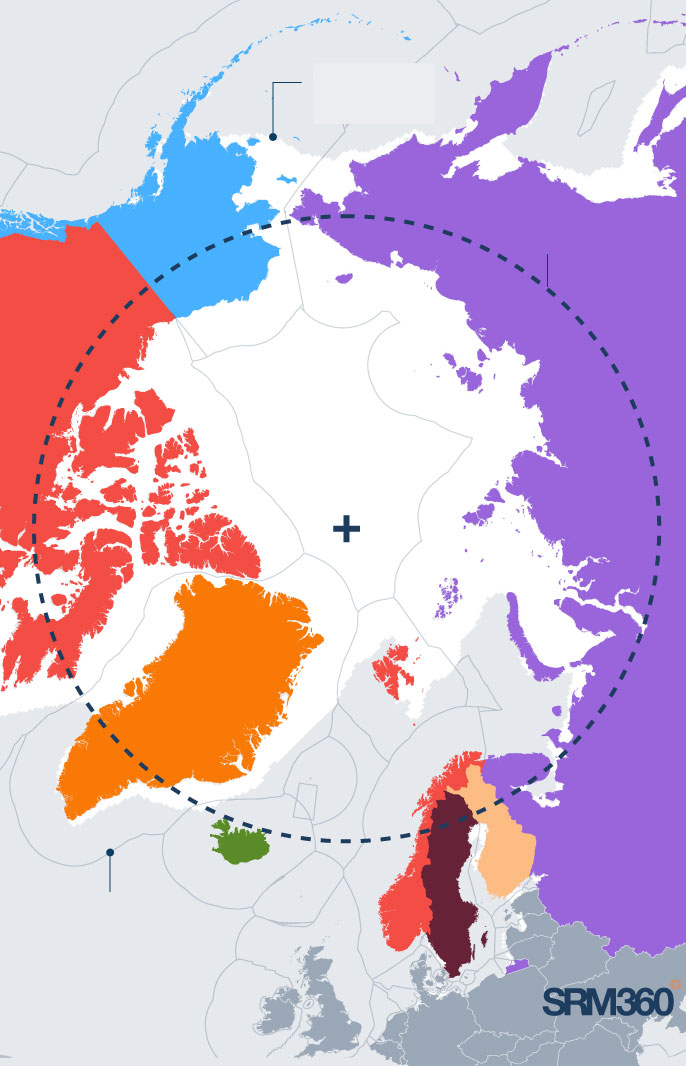

Sea ice extent

(January 2025)

U.S.

(Alaska)

ARCTIC CIRCLE

Canada

Arctic Ocean

NORTH POLE

Russia

Denmark

(Greenland)

Norway

Iceland

Sweden

Finland

Exclusive Economic Zones

Sources: Natural Earth; NOAA; Flanders Marine Institute

Japan

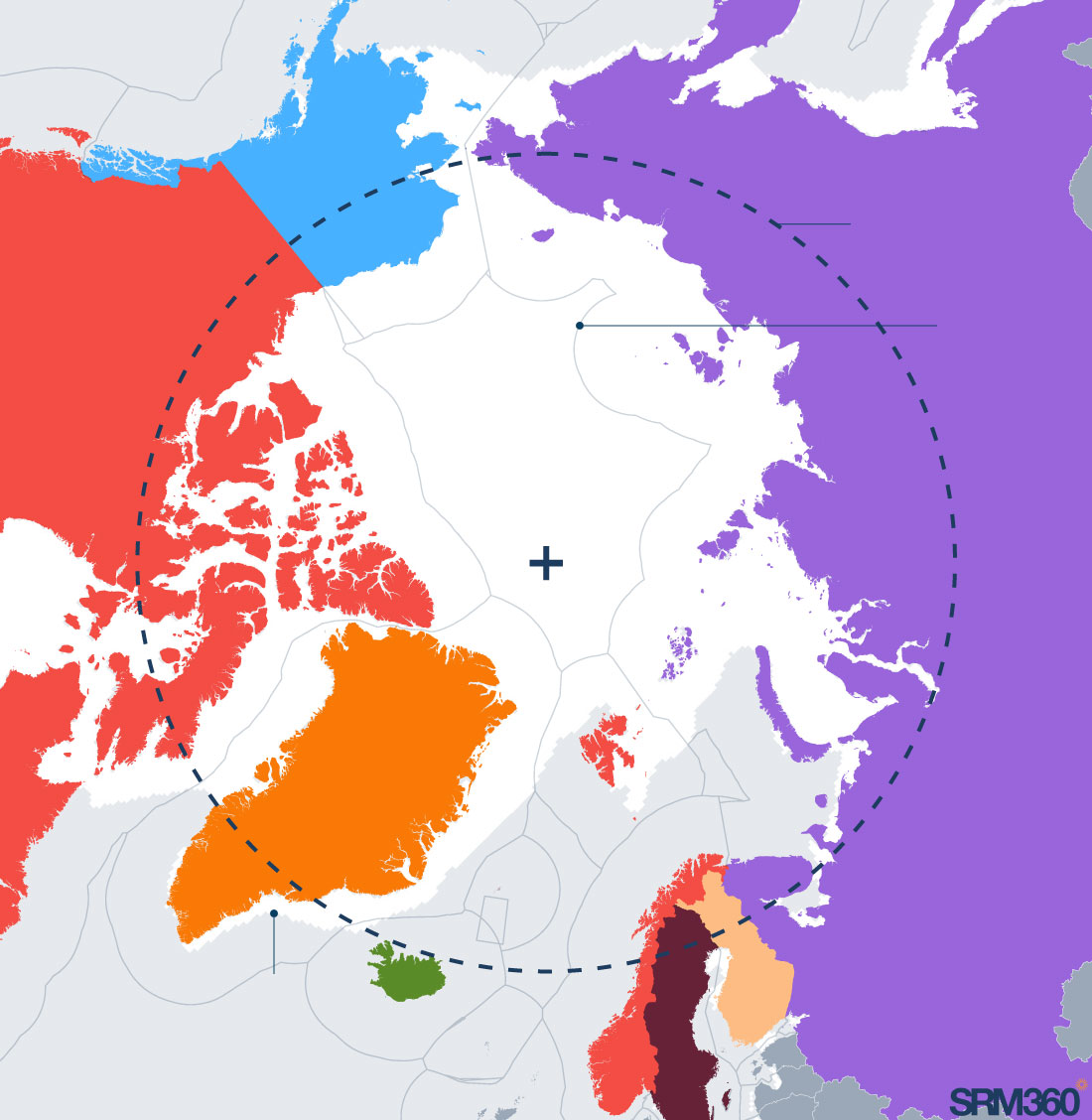

Sea ice extent

(January 2025)

Pacific Ocean

S. Korea

N. Korea

U.S.

(Alaska)

ARCTIC CIRCLE

China

Canada

United States

Arctic Ocean

Mongolia

NORTH POLE

Russia

Denmark

(Greenland)

Kazakhstan

Kyrgystan

Tajikistan

Norway

Uzbekistan

Tukmenistan

Iceland

Sweden

Finland

Exclusive Economic Zones

Atlantic Ocean

Iran

Sources: Natural Earth; NOAA; Flanders Marine Institute

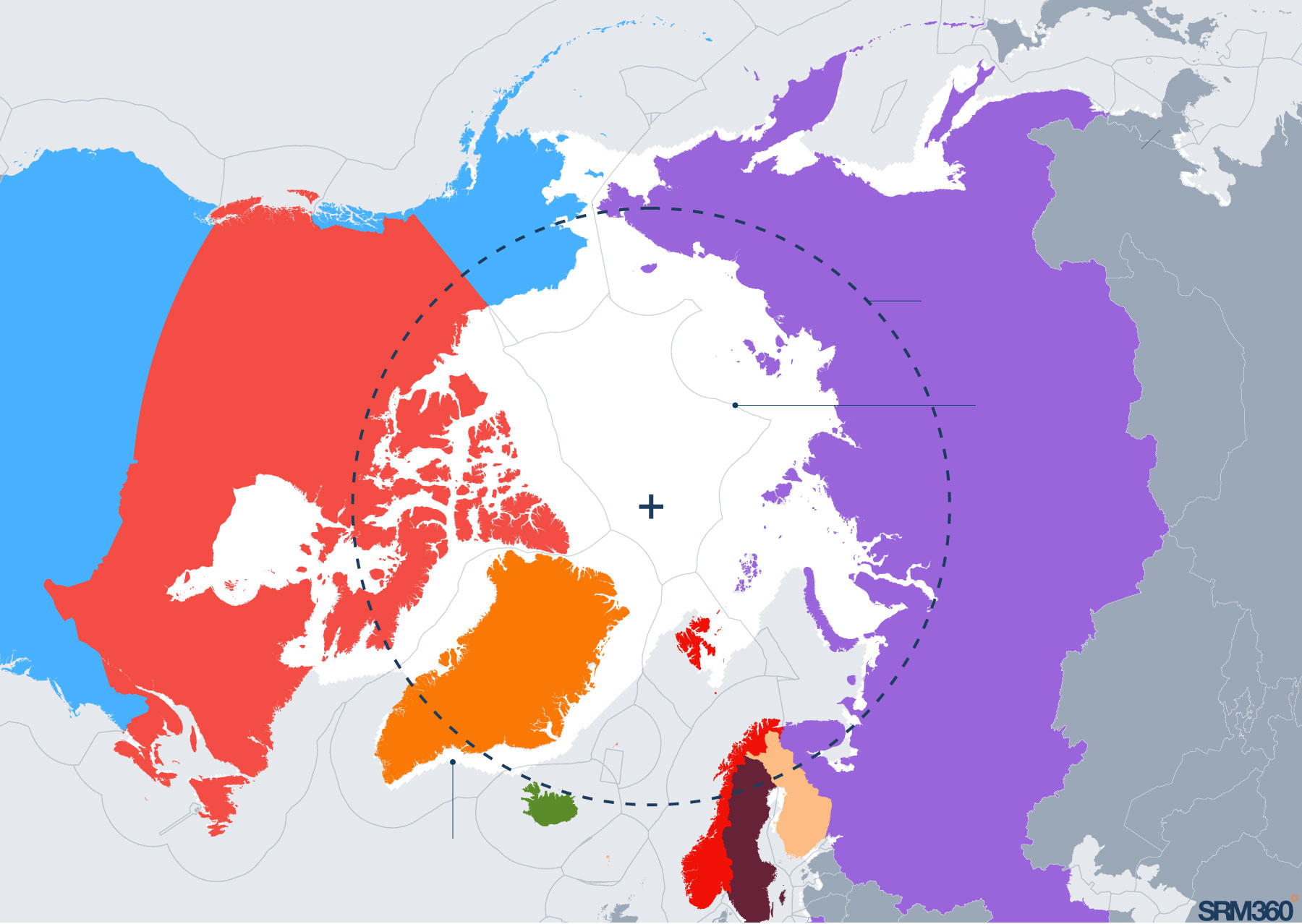

N. Korea

Pacific Ocean

U.S.

(Alaska)

ARCTIC CIRCLE

China

Exclusive Economic Zones

Canada

United States

Arctic Ocean

Mongolia

NORTH POLE

Russia

Kyrgystan

Denmark

(Greenland)

Tajikistan

Kazakhstan

Norway

Sweden

Iceland

Uzbekistan

Finland

Sea ice extent

(January 2025)

Tukmenistan

Est.

Atlantic Ocean

Lat.

Belarus

Lith.

Iran

Sources: Natural Earth; NOAA; Flanders Marine Institute

An outdated view of Arctic politics

Our research found that SRM scientists and entrepreneurs understand the Arctic as an exceptional region in international politics, where inter-state cooperation on environmental and scientific agendas can be separated from international security and competitive dynamics between states. This idea of “Arctic exceptionalism”,12 famously encapsulated in Mikhail Gorbachev declaring the Arctic a “zone of peace”, was prevalent in the decades after the Cold War and led to many successful examples of inter-state cooperation – particularly through the Arctic Council of states and Indigenous organisations.

However, recent political developments on the global stage have made “Arctic exceptionalism” appear increasingly outdated. The relationship between the Arctic NATO states and Russia has soured markedly since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2014. It further deteriorated with the full-scale invasion in 2022, which caused NATO states to temporarily suspend their participation in the Arctic Council. State strategies for the Arctic increasingly see it as having a high risk of conflict, and there is a clear trend toward more military presence in the Arctic.10

We also found that mitigating climate change is not a major priority in Arctic state policies. Instead, the changing Arctic climate is largely seen as a new condition which must be adapted to or even seized upon strategically as an opportunity – as illustrated by US President Trump’s continued efforts to gain control of Greenland. The warmer climate makes the Arctic more accessible, enabling new strategies for creating economic growth from the region, for example through extraction of oil, gas, or minerals; new transcontinental shipping routes; and tourism. This creates security risks and competition which states respond to by increasing surveillance and military presence, which, in turn, creates more mistrust of motives among the NATO states and Russia.10

Destabilising or just unlikely?

To anticipate how Arctic SRM would unfold in reality, we must place it in this broader geopolitical context. As my colleagues and I found in a related interview study of security experts,13 security actors and climate scientists don’t make sense of SRM in the same way. Scientists and engineers are predominantly concerned with technical uncertainties and aggregate impacts as they can be measured with models and experiments, bracketing out human motives and interpretations. By contrast, diplomats, security analysts, and military actors make sense of SRM through their pre-existing geopolitical logics. This means, among other things, that they think of SRM first and foremost as a strategic source of leverage in global politics. Rather than assuming it would be used to mitigate climatic shifts in a rational way, they are concerned that states will not trust each other’s intentions around SRM research and deployment, and that the potential spread of disinformation about SRM will make climate politics and international cooperation more difficult.

Therefore, if a state were to allow deployment or large-scale experiments with SRM in the increasingly conflictual Arctic, the outcome would be unpredictable but likely destabilising. It could trigger a diplomatic crisis, potentially sabotaging other efforts to cooperate on environmental policy and research. States might also consider their options for “counter-geoengineering”,14 which would compound the technical uncertainties of SRM. However, anticipation of such dynamics could also make states prevent any deployment or experiments from getting off the ground in the first place.13

Could Arctic SRM continue a history of colonialism and exploitation?

If Arctic SRM did get off the ground, it is important to ask what kind of SRM would be feasible and how it would be implemented. In comparing the scientific literature on SRM with state policies, we saw that both had a heavy emphasis on technological solutionism, i.e. attempting to solve complex social problems through technological innovation. They also, although to varying degrees, tended to see the Arctic as a solution for problems outside of the region – whether that is reducing global climate impacts or supplying energy and minerals. Thus, it is conceivable that states may adopt SRM in an attempt to keep the Arctic temperature stable, but still high enough to maintain the possibility of extractive projects and shipping.

If that succeeded, the Arctic climate would be altered to serve ends outside the region itself, on the order of states which have often acquired their Arctic territories through an interplay between scientific exploration and colonisation.15 It is hard to understand such a scenario as anything other than a continuation of such colonial projects. The criticism from Indigenous organisations over existing Arctic SRM experiments – including the Saami Council-led opposition to SCoPEx and the Alaska Native Organisations-led demand to stop the Arctic Ice Project – demonstrates a lack of effective inclusion of Indigenous and local populations in the design and control of SRM. While some researchers have done more to include local and Indigenous communities in research, the risk of any potential Arctic SRM becoming a colonial and extractivist project remains great.

Promotion of Arctic SRM is imprudent

SRM scientists and entrepreneurs face formidable technical challenges, but the Arctic is also not a political safe zone for SRM. The combination of technical uncertainty and political infeasibility makes it at the very least imprudent to rely on Arctic SRM as part of a backstop or “insurance policy” for climate change. It is essential that efforts to deal with climate change in the Arctic first and foremost focus on global emissions reductions and adaptation, the latter with effective control by local and Indigenous communities.

To reduce the high risk of geopolitical conflict and unjust political decision-making, any research into SRM in the Arctic should be conducted transparently between nations and be under effective, democratic control of local and Indigenous populations. It should also be approached in ways that minimise the risk of it distracting from more important and immediate options for mitigating climate change through global emissions reductions and adaptation. If technical humility and geopolitical realism are lacking, promotion of Arctic SRM would pose more risks for climate politics than solutions.

The views expressed by Perspective writers and News Reaction contributors are their own and are not necessarily endorsed by SRM360. We aim to present ideas from diverse viewpoints in these pieces to further support informed discussion of SRM (solar geoengineering).

Endnotes

- Latham J, Gadian A, Fournier J, et al. (2014). Marine cloud brightening: regional applications. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 372(2031):20140053. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2014.0053

- Field L, Ivanova D, Bhattacharyya S, et al. (2018). Increasing Arctic sea ice albedo using localized reversible geoengineering. Earth’s Future. 6(6):882-901. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018EF000820

- Desch SJ, Smith N, Groppi C, et al. (2017). Arctic ice management. Earth’s Future. 5(1):107-27. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016EF000410

- van Wijngaarden A, Moore JC, Alfthan B, et al. (2024). A survey of interventions to actively conserve the frozen North. Climatic Change. 177(4):58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-024-03705-6

- Zampieri L, Goessling HF. (2019). Sea ice targeted geoengineering can delay Arctic sea ice decline but not global warming. Earth’s Future. 7(12):1296-306. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019EF001230

- Webster MA, Warren SG. (2022). Regional geoengineering using tiny glass bubbles would accelerate the loss of Arctic sea ice. Earth’s Future. 10(10). https://doi.org/10.1029/2022EF002815

- Bodansky D, Hunt H. (2020). Arctic climate interventions. The International Journal of Marine and Coastal Law. 35(3):596-617. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718085-BJA10035

- Moore JC, Mettiäinen I, Wolovick M, et al. (2021). Targeted geoengineering: local interventions with global implications. Global Policy. 12:108-18. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12867

- Versen J, Mnatsakanyan Z, Urpelainen J. (2022). Concerns of climate intervention: understanding geoengineering security concerns in the Arctic and beyond. Climatic Change. 171(3):27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-022-03345-8

- Kornbech N, Corry O, McLaren D. (2024). Securing the ‘great white shield’? Climate change, Arctic security and the geopolitics of solar geoengineering. Cooperation and Conflict. https://doi.org/10.1177/00108367241269629

- We examined the littoral Arctic states, i.e. those with a coastline facing the Arctic Ocean: Canada, Russia, Norway, Denmark (through its possession of Greenland), and the United States.

- Hoogensen Gjørv G, Hodgson KK. (2019). ‘Arctic exceptionalism’ or ‘comprehensive security’? Understanding security in the Arctic. https://hdl.handle.net/10037/17564

- Corry O, McLaren D, Kornbech N. (2024). Scientific models versus power politics: How security expertise reframes solar geoengineering. Review of International Studies. 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210524000482

- Parker A, Horton JB, Keith DW. (2018). Stopping solar geoengineering through technical means: a preliminary assessment of counter‐geoengineering. Earth’s Future. 6(8):1058-65. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018EF000864

- Stuhl A. (2019). Unfreezing the Arctic: Science, colonialism, and the transformation of Inuit lands. University of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/U/bo24957300.html