Article

SRM Bans and Moratoria: Calls to Restrict Solar Geoengineering Activities

Concerns about sunlight reflection methods (SRM) or solar geoengineering have led to proposals to prohibit its deployment as well as field experiments. What are the different forms of prohibition and how might these calls affect SRM research and potential deployment?

Photo: Bill Oxford

Key takeaways

- Bans prohibit something on a permanent basis, while moratoria prohibit something only on a temporary basis until certain conditions are met.

- Many US states are considering bans that would cover SRM, partly inspired by the "chemtrails" conspiracy theory.

- Calls for moratoria on large-scale field experiments and deployment, with exceptions for small-scale field experiments, have more traction with policymakers.

SRM Guide

How Should SRM Be Governed?

In the early 1970s, controversy arose over “recombinant DNA” (rDNA), an emerging technology that involved the combining of genetic material from different species.1 The use of rDNA held tremendous promise for advances in science and medicine but triggered serious concerns about potential public health, safety, and environmental hazards. To address these concerns, in 1974 researchers adopted a moratorium on certain experiments using rDNA technology.1

Like rDNA, SRM (solar geoengineering) has the potential to provide immense benefits while also posing considerable risks. While SRM is not banned under international law, participants in discussions about SRM have proposed an array of moratoria or bans on different aspects of the technology over the past two decades. What are these proposals, and how would their adoption affect the development of SRM?

Bans and moratoria

Moratoria and bans are two types of prohibition, defined as an act that forbids something. A moratorium is a temporary prohibition, while a ban is a permanent one.

They both involve ordering a stop to an activity but have different purposes. A ban is intended to stop something from happening indefinitely because it is regarded as morally impermissible or because it is considered to pose unacceptable risks.

By contrast, a moratorium is intended to pause an activity to learn more about the risks associated with it and/or to reduce tensions to allow for bargains to be struck.2 However, a moratorium might also reflect a partially successful attempt to ban something.

As types of prohibition, moratoria and bans both vary in important ways. Any prohibition must specify its scope, or the range of activities it covers, as well as the actors to which it applies.

Additionally, a moratorium must specify the conditions under which it could be lifted. Conditions for lifting can vary from permissive, for example, once a short period of time has passed, to restrictive, for example, only after very demanding or vaguely specified criteria have been met.

At the extreme, conditions can be so onerous or undefined that they are impossible to meet in practice – in this instance, a moratorium may constitute a de facto ban. This occurred, for example, in the case of germ line gene therapy.3,4

Calls for a moratorium on SRM activities

Over the years, there have been several calls or proposals for moratoria on SRM, as summarised in the table below.

Calls and Proposals for Moratoria on SRM

| Associated Body | Year | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) | 2010 | Decision X/33 called for a moratorium on SRM activities that may affect biodiversity, except for small-scale outdoor experiments.

Conditions for lifting include adequate governance, scientific justification, risk assessment. |

| Climate Overshoot Commission | 2023 | SRM Recommendation 1 proposed a moratorium on interventions posing risk of significant transboundary harm, inapplicable to small-scale outdoor experiments.

Conditions for lifting include scientific justification, adequate governance. |

| Group of Chief Scientific Advisors to the European Commission | 2024 | Proposed EU-wide moratorium on deployment and large-scale experiments, inapplicable to small-scale outdoor experiments.

Conditions for lifting include a scientific and political consensus. |

| Group of Chief Scientific Advisors to the European Commission | 2024 | Proposed global non-deployment agreement including for large-scale experiments, not applicable to small-scale outdoor experiments.

Conditions for lifting are not specified. |

In 2010, parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) adopted Decision X/33 inviting countries to consider prohibiting “climate-related geo-engineering activities [including SRM] that may affect biodiversity”, except for carefully regulated small-scale field experiments. This non-binding decision specified that such a prohibition could be lifted if there was adequate governance, scientific justification, and consideration of risks. In effect, the parties to the CBD called on countries to consider adopting such a moratorium. To date, no countries have done so.

More than a decade later, the non-governmental Climate Overshoot Commission recommended that countries adopt a moratorium on SRM deployment and large-scale outdoor experiments. More precisely, such a moratorium should apply to any intervention posing a risk of “significant transboundary harm”, that is, harm to other states’ environments and areas beyond their national jurisdiction. Like CBD Decision X/33, the recommended moratorium would be lifted if doing so was supported by a strong scientific knowledge base and an adequate governance framework.

At the end of 2024, the Group of Chief Scientific Advisors to the European Commission recommended pursuing two separate but related moratoria. First, they called for an “EU-wide moratorium” on SRM, with an exception for carefully regulated small-scale outdoor experiments, to be lifted only if there is a scientific and political consensus to do so. Second, they advocated for a global “non-deployment agreement” in the longer term that would prohibit interventions by states and private entities but allow for carefully controlled small-scale outdoor experiments; no conditions for lifting were specified. The European Commission is currently reviewing these recommendations.

Calls for a ban on SRM

There have also been several more restrictive proposals to prohibit SRM. Most of these would impose self-described bans. While proponents of an International Non-Use Agreement on Solar Geoengineering do not describe it as such, in failing to specify conditions for lifting (and in other ways), their proposal would amount to a de facto ban. These proposals are summarised in the table below.

Proposals to Ban SRM

| Associated Body | Year | Details |

|---|---|---|

| US states | 2014– | State-level bans would prohibit outdoor interventions. |

| Initiative for a Solar Geoengineering Non-Use Agreement | 2022 | Proposed International Non-Use Agreement on Solar Geoengineering would prohibit public research funding, outdoor experiments, patent rights, deployment, normalisation. |

SRM360 Tool

US proposals to ban solar geoengineering

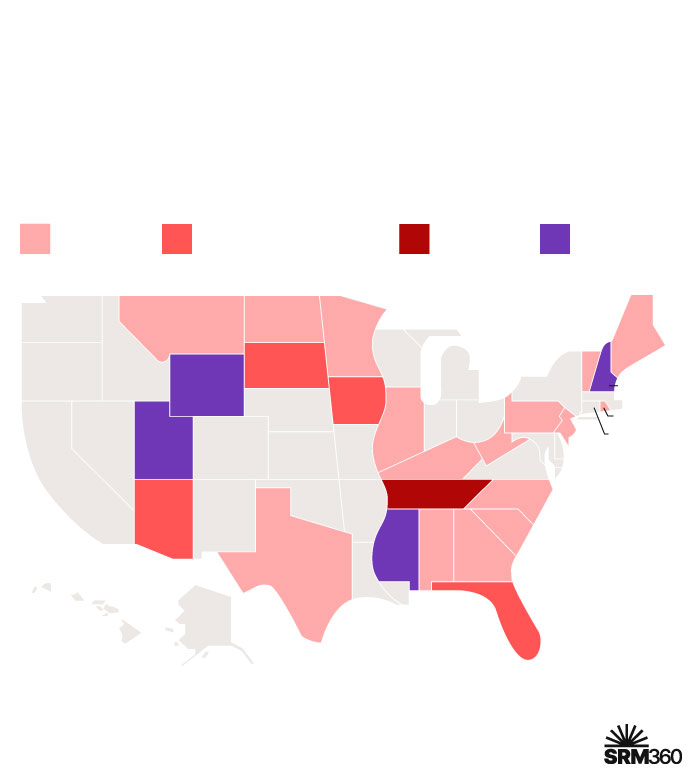

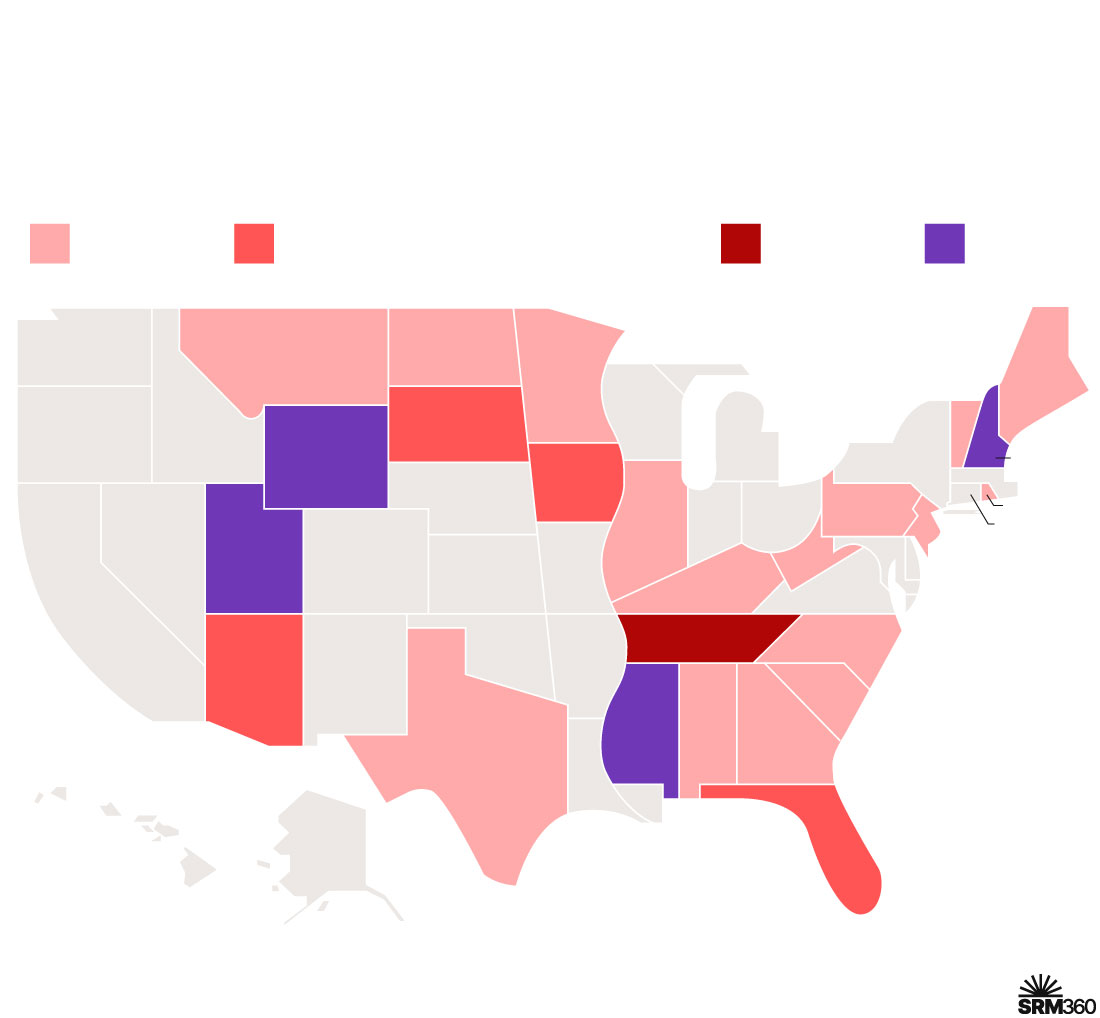

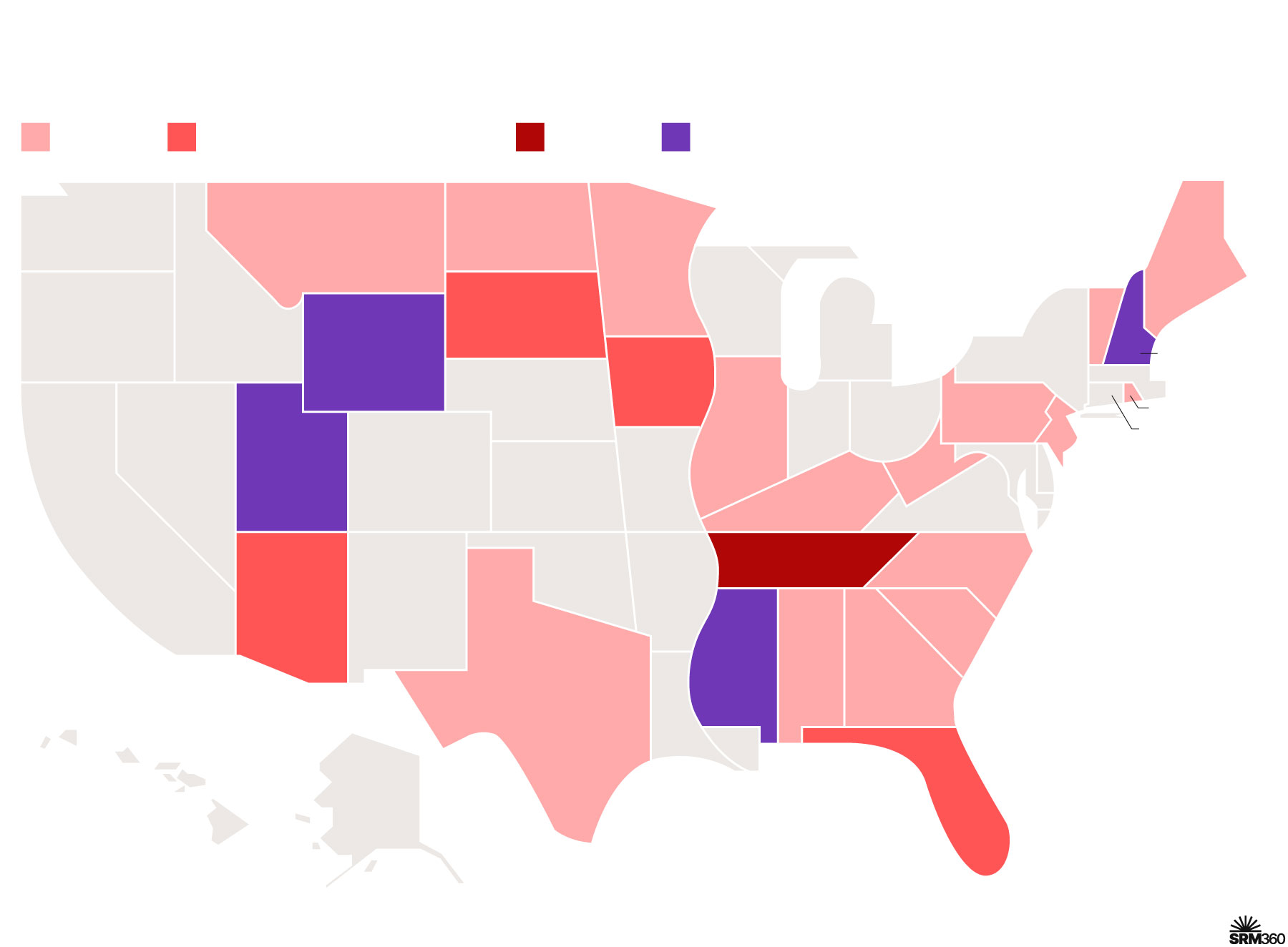

Starting in the mid-2010s, several US state legislatures have considered bills that would ban all outdoor SRM interventions, and this number has surged recently.5 Although they vary somewhat in their specifics, all these bills employ language and articulate concerns tied to the chemtrails conspiracy theory community – their promotion appears to be loosely coordinated by networks of conservative activist groups. Penalties for violating these bans can be significant. Tennessee has passed one of these state-level bills.

Proposals to ban solar geoengineering in the US

Thirty-four US states have proposed banning solar geoengineering since 2023.

Proposed

Passed by state house or senate

Failed

Approved

Wash.

Mont.

N. D.

Maine

Mich.

Minn.

Wis.

Vt.

S. D.

Ore.

Idaho

N.H.

Wyo.

N.Y.

Mass.

Iowa

Neb.

R.I.

Pa.

Ohio

Ind.

Conn.

N.J.

Ill.

Md.

W. V.

Nev.

Utah

Colo.

Del.

Kan.

Mo.

Ky.

Va.

Tenn.

N. C.

Calif.

Okla.

Ark.

Ariz.

N.M.

S. C.

Ala.

Miss.

Ga.

Texas

La.

Fla.

Hawaii

Alaska

Note As of 24 June 2025

Source: SRM360.org

Proposed

Passed by state house or senate

Approved

Failed

Wash.

Mont.

N. D.

Maine

Minn.

Wis.

Vt.

S. D.

Ore.

Idaho

Mich.

Wyo.

N.H.

N.Y.

Iowa

Mass.

Neb.

R.I.

Pa.

Ohio

Ind.

Conn.

N.J.

Ill.

Md.

W. V.

Nev.

Utah

Colo.

Del.

Kan.

Mo.

Ky.

Va.

Tenn.

N. C.

Calif.

Okla.

Ark.

Ariz.

N.M.

S. C.

Ala.

Miss.

Ga.

Texas

La.

Fla.

Hawaii

Alaska

Note As of 24 June 2025

Source: SRM360.org

Proposed

Passed by state house or senate

Approved

Failed

Washington

Montana

N. Dakota

Maine

Vermont

Minnesota

Wisconsin

S. Dakota

Oregon

Idaho

Michigan

Wyoming

New Hampshire

New York

Iowa

Massachusetts

Nebraska

Rhode Island

Pennsylvania

Ohio

Indiana

Connecticut

Illinois

New Jersey

Maryland

W. Virginia

Nevada

Utah

Colorado

Delaware

Kansas

Missouri

Kentucky

Virginia

Tennessee

N. Carolina

California

Oklahoma

Arkansas

Arizona

New Mexico

S. Carolina

Alabama

Mississippi

Georgia

Texas

Louisiana

Florida

Hawaii

Alaska

Note As of 24 June 2025

Source: SRM360.org

In 2022, a group of academics called for countries to adopt an International Non-Use Agreement (NUA) on Solar Geoengineering.6 Signatories to the NUA would commit to prohibit public research funding for SRM, outdoor experiments, patent rights, deployment including that of technologies developed by third parties, and the “institutionalisation” of SRM as a policy option in international bodies.

Although its proponents contend that “the duration of such a non-use agreement … would remain open to political debate and further decision-making”, they specify no pathway for lifting the prohibition while declaring that: “At its core would be the mutual assurance of its signatories that they would not develop or deploy solar geoengineering technologies in the future”.6 As such, the NUA is best understood as a ban. At the time of writing, no countries have adopted it.

In addition, it is worth noting that in 2022 the Mexican government announced its intention to ban SRM, although it remains unclear whether it has done so.

Implications of these proposed bans and moratorium

If imposed, the bans discussed above – US state-level bans as well as the NUA – would have variable effects. To the extent that state-level bans are targeting outdoor interventions, which their sponsors believe are taking place but are not in fact occurring, they would have (and, in the case of Tennessee, are having) little practical impact.

The NUA, however, is more grounded and comprehensive than these state-level bans. By seeking to ban not just outdoor interventions but also public funding for research, patent rights, and the “normalisation” of SRM, adoption of the NUA could have a severe chilling effect on research.

In contrast, the various moratoria might support expanded research on SRM. By prohibiting deployment and large-scale field experiments, while explicitly carving out exceptions for small-scale research including outdoor experiments, such moratoria could reassure sceptical publics that deployment is neither happening nor permitted. They might help create a safe space for researchers to learn more about the risks and potential benefits of SRM and possible ways of addressing its governance challenges.

The consequences of CBD Decision X/33 have been primarily political. Specifically, it has prompted some actors to push for restrictive measures on SRM, and it has been framed misleadingly as a de facto moratorium by some groups.

Prospects

In 1975, a year after the moratorium on rDNA was adopted, scientists met at a conference in Asilomar, California, where they judged that the risks associated with rDNA were manageable and agreed to lift the moratorium under strict guidelines.1,7 In the decades since, rDNA technology has proven to be enormously beneficial for public health and entail minimal risk.

The case of rDNA suggests that a carefully designed moratorium might help ease fears and enable responsible research. For those opposed to expanded research, however, a more restrictive moratorium or ban is likely to be preferred. Ultimately, both types of prohibition reflect an underlying desire to proceed with caution, a sentiment that is widely shared across the SRM community.

Open questions

- What is the political significance of the many state-level bans being proposed (and in the case of Tennessee passed) in the United States? Do they have international implications?

- How will the European Commission respond to recommendations for moratoria on SRM deployment and large-scale field experiments?

- If countries pursue a moratorium on certain SRM activities, how should the conditions for lifting that moratorium be defined?

Endnotes

- Berg P, Singer MF. (1995). The Recombinant DNA Controversy: Twenty Years Later. Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences 92: 9011-9013. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.92.20.9011

- Herzog MM, Parson EA. (2016). Moratoria for Global Governance and Contested Technology: The Case of Climate Engineering. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2c28w2tn

- Germ line gene therapy involves intentional changes to human DNA that are designed to be inherited.

- Cook-Degan RM. (1997). Do Research Moratoria Work? In Cloning Human Beings. https://bioethicsarchive.georgetown.edu/nbac/pubs/cloning2/cc8.pdf

- States that have considered such bills include Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Iowa, Kentucky, Maine, Minnesota, Mississippi, Montana, New Hampshire, New Jersey, North Carolina, North Dakota, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Vermont, West Virginia, and Wyoming.

- Biermann F, Oomen J, Gupta A, et al. (2022). Solar Geoengineering: The Case for an International Non-Use Agreement. WIREs Climate Change 13: e754. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.754

- In 2010, researchers held a meeting on “climate intervention” technologies including SRM at Asilomar, modelled on the 1975 rDNA conference, which produced a set of recommended guidelines for research.