Podcast

News Roundup: History of SRM

A look-back over the entire history of sunlight reflection methods research and ahead to its future.

For the first News Roundup episode of Climate Reflections, host Pete Irvine and guests look back over the entire history of SRM and ahead to its future. For this, Pete is joined by 4 guests with extensive experience working on this topic:

- Inés Camilloni, a Professor at the Department of Atmospheric and Ocean Sciences of the University of Buenos Aires and a Vice-Chair of the Intergovernmental panel on climate change’s working group on physical science.

- Govindasamy Bala, a Professor at the Centre for Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences at the Indian Institute of Science who has worked on SRM longer than almost any other researcher, publishing his first article on this topic 24 years ago.

- Oliver Morton, the Senior and Briefings editor at the Economist who has written extensively about SRM, including in his excellent 2016 book “The Planet Remade”

- Cynthia Scharf, a senior fellow at the International Center for Future Generations, where she leads their work on SRM. She was previously senior strategy director for the Carnegie Climate Governance (C2G) Initiative, and served in the Office of the UN Secretary-General as the head of strategic climate communications.

Transcript

Dr. Pete Irvine: [00:00:00] Welcome to the first news roundup of the Climate Reflections podcast where we discuss the latest developments around sunlight reflection methods with experts in the field. I’m your host, Dr. Pete Irvine. I’m a climate scientist and I’ve been studying SRM since 2009. For this first episode of Climate Reflections, rather than looking back over a month of developments in the field, we’re going to look back over the entire history of SRM and ahead to its future.

For this, I’m joined by four guests with extensive experience working on this topic. First up, we have Inés Camilloni, a Professor at the Department of Atmospheric and Ocean Sciences of the University of Buenos Aires and a Vice Chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Changes Working Group on Physical Science. Hi there, Ines.

Inés Camilloni: Hi.

Dr. Pete Irvine: Next up, Govindasamy Bala, a Professor at the Center for Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences at the Indian Institute of Science, who has worked on SRM longer than almost any other researcher, publishing his first article [00:01:00] on this topic over 20 years ago.

Govindasamy Bala: 24 years.

Dr. Pete Irvine: 24 years. Oh, that’s right. Then we have Oliver Morton, the senior and briefings editor at The Economist, who has written extensively about SRM, including in his excellent 2016 book, The Planet Remade.

Oliver Morton: Hi Pete. Uh, I should also mention that I’m a trustee of The Degrees Initiative, which is an organization which, uh, funds geoengineering research in the Global South.

Dr. Pete Irvine: And last but not least, we have Cynthia Scharf, a senior fellow at the International Center for Future Generations, where she leads their work on SRM. She was previously senior strategy director for the Carnegie Climate Governance Initiative and served in the office of the UN Secretary General as the head of strategic climate communications.

Cynthia Scharf: Glad to be here.

Dr. Pete Irvine: And I should mention, all four of our guests are advisors to SRM 360, and we’re glad to have them. So, first, I’d like to turn to Ollie. How did the idea that global warming could be counteracted by reflecting [00:02:00] sunlight first emerge?

Oliver Morton: Well, I think, Pete, you have to put that into the broader context of how people have thought about climate change throughout the 20th century. And one of the important things there is the idea that human directed climate change might well at any point become a possibility. There’s always this thinking both in the West and in the, Soviet bloc, that immense new sources of energy, for which read nuclear energy, will allow humans to engineer the climate of the planet.

It then turns out in the 1950s that humans are already potentially doing something to the climate of the planet, when Roger Revelle brings out his famous paper talking about the idea that, uh, carbon dioxide is building up in the atmosphere, and this is a quote, “great experiment,” the most quoted line ever given about climate change. And as soon as that happens, people start thinking about how you might cool the climate and indeed, when Revelle [00:03:00] participates in a study for the Presidential Council of Advisors on Science and Technology for Lyndon Johnson, it is by reflecting sunlight away from the surface of the earth that the effects of warming because of carbon dioxide.

Dr. Pete Irvine: I guess something just on that report, am I right that they didn’t mention cutting CO2 emissions?

Oliver Morton: Good God, are you a communist, man? No, of course they didn’t, uh, they didn’t mention cutting CO2 emissions. The idea that you’re going to sort of, like, radically change the fundamental nature of, uh, the, the, the great American economy in the 1950s and 60s, that’s, that’s just not under discussion. No, the idea is that if, as I say, it’s the idea of the Earth as a geophysical entity which can be manipulated is very much the mindset that people are thinking in at that time. It’s only after the great anti technocratic turn of the early 1970s that people begin to come up with the idea that maybe that’s not such a good way of looking at the Earth after all.

Dr. Pete Irvine: And I [00:04:00] guess in the, so I guess if 1965 marks the start of when countries started thinking about climate change and SRM was at the front of their mind and emissions cuts were at the back of their mind, that could have changed over the coming decades and SRM was more suppressed.

Oliver Morton: I mean, people are thinking about climate change, deliberate climate change, before they’re thinking very much about inadvertent climate change.

So the Soviet history of this sort of thinking is very much involved with the idea that the Soviet Arctic could be warmed up, and that’s a constant area of geophysical speculation in the Soviet Union, um, from the 1930s through to the 1960s. So the idea that thinking about climate change is just thinking about greenhouse warming is one that gives you, that gives you a distorted view when you’re looking at the history of this sort of thinking.

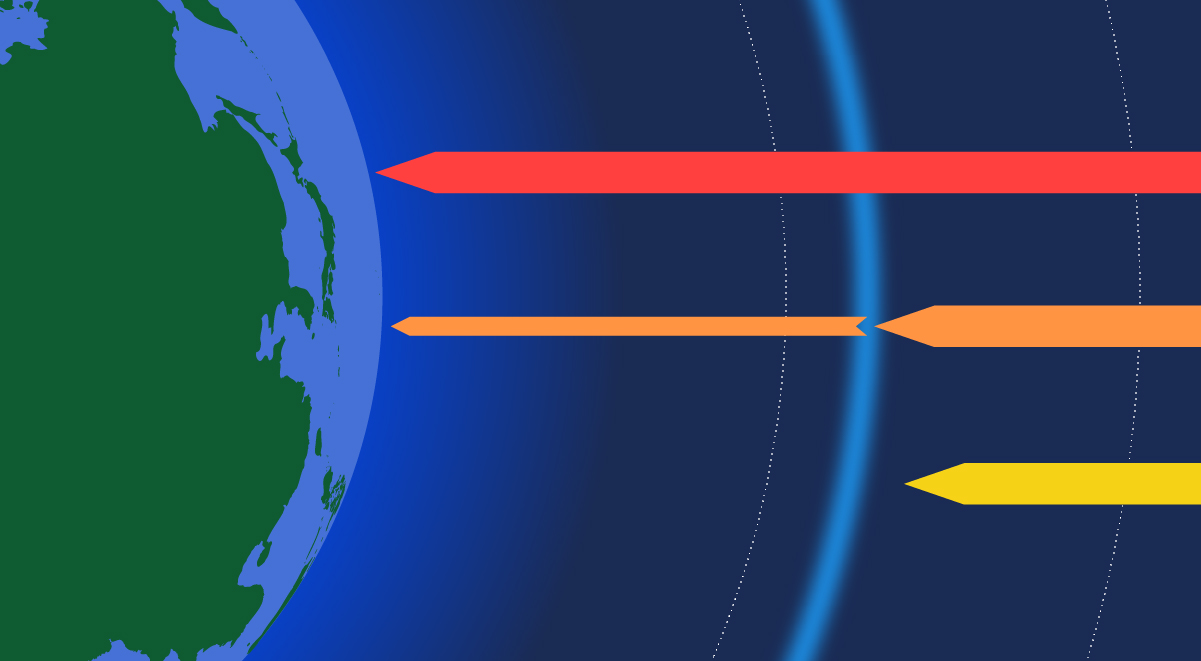

The, the other thing you have to keep in mind is the importance of planetary science. The first time this becomes a really big issue is when people, uh, when the first orbiter, first American orbiter, Mariner 9, goes into orbit around Mars. [00:05:00] And there’s a dust storm all around the planet. And as the dust storm subsides, they see the amount of light being reflected from the planet reducing, and the warmth of the surface increasing.

And as one of the scientists involved, Brian Toon, says, this is the first time science has ever been able to observe a global climatic change which it understands, and that’s a big thing. In the West, ideas about how volcanoes influence the climate come out of that understanding of Mars, and to a lesser extent, Venus.

Dr. Pete Irvine: 1991, speaking of volcanoes, uh, there was a major volcanic eruption, the largest of the 20th century, I believe. Um, what impact has that had on the discussion of SRM.

Oliver Morton: Great impact on the discussion of, uh, solar geoengineering. Also, a great impact on the discussion of climate itself, because James Hansen, who had done work on Venus and on modeling the climate has since the 1970s been interested in the question of what volcanoes do to the climate.

And with Mount [00:06:00] Pinatubo, he actually has a test case and so he sort of echoes Revelle. ” and he predicts. using the GISS climate model that the temperature of the earth will drop, um, by a bit over the next year or so as a result of this eruption.

And so that, in, when you’re thinking about solar geoengineering, about SRM, that eruption is seen as sort of being the great, sort of, proof of principle that yes, we see sulfate spread around the world, and, uh, and, and the world cools. And that’s a very important aspect of it. The other thing is it’s really the first direct test of how well global circulation models work as computer models.

And that’s what Hansen’s particularly interested in and that is actually a really, a defining. thing for the world going into the 1990s when predictions from GCMs will be, uh, very hotly debated as the basis of [00:07:00] policy. Having a natural experiment which shows that they do kind of get the climate right because they show this cooling effect, that’s absolutely vital.

Dr. Pete Irvine: So then another, another big development was when Paul Crutzen, who won the Nobel Prize for his work on ozone, wrote a famous commentary in 2006, um, suggesting it was time to start thinking about SRM. Uh, what was his argument, uh, and what was the significance of his intervention?

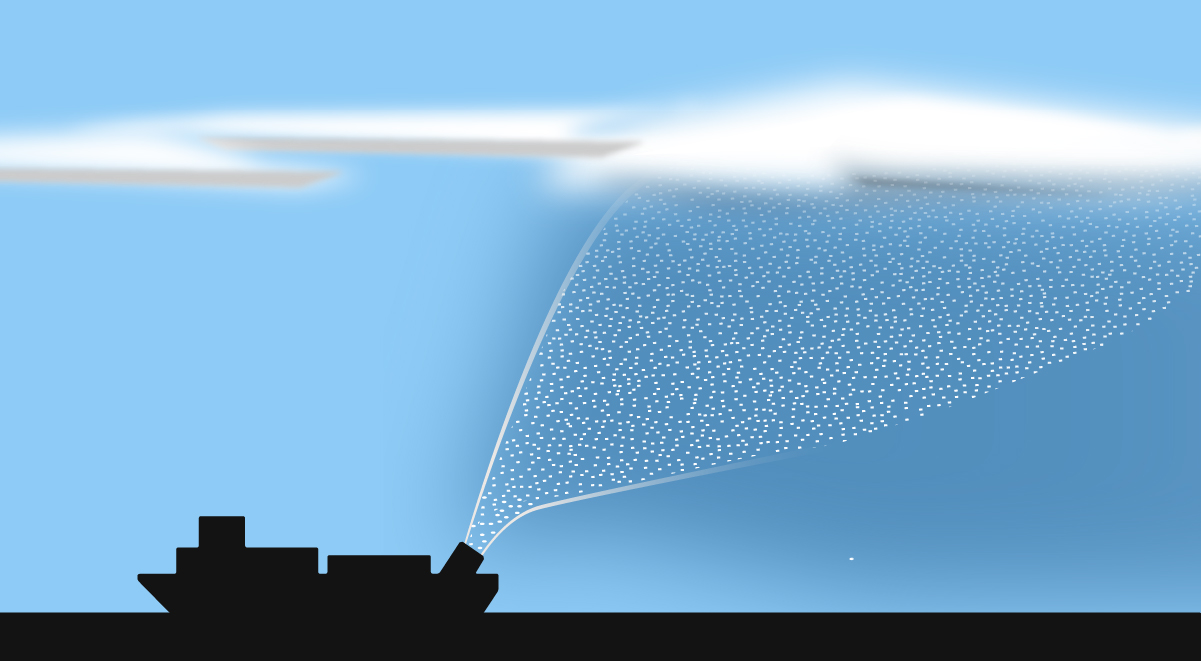

Oliver Morton: It’s a subtle argument. He’s saying that at the moment, humans are putting a great deal of sulfur dioxide into the lower atmosphere, the troposphere. And this is doing many of those humans a lot of harm because breathing in particulates created by that sort of aerosol reduces the life expectancy of millions of people around the world.

And so he’s noting that also, uh, that the people are cleaning this up and that that’s good for the health of the people living on the surface of the planet, which is to say, everyone. [00:08:00] But at the same time, you’re losing the reflective effect of those sulfate aerosols. So you will be warming up the planet as you unmask the greenhouse warming by no longer reflecting away sunlight.

And this is a discussion that’s been going on back to the 1970s that’s made very clearly by Tom Wigley in the 1990s. But Crutzen then goes forward and says, and it’s not clear whether he’s suggesting it or whether he’s doing a thought experiment or whether he’s doing a sort of like reductio ad absurdum to freak people out, but he says sulfate aerosols last a lot longer in the stratosphere and so if we put a lot less sulfur into the stratosphere we could keep the cooling effect of the sulfates low down that are killing people, but without the killing people.

And he makes a couple of other very crucial points here. One is that he says that’s not a reason for not, uh, controlling carbon [00:09:00] dioxide emissions, because, as he points out, carbon dioxide also acidifies the oceans. So even if you could balance out the temperature effects completely, you would still want to reduce carbon dioxide because of the effects on the oceans. All the time, remember, it’s possible Crutzen was saying this to freak people out so that they would double down on carbon dioxide reduction. If that was his goal, that’s certainly something that did not subsequently happen.

Dr. Pete Irvine: And then shortly after, I think we shift, at least from my perspective, from the pre-history of SRM to the history of SRM, when I started in 2009, um, with the, publication of the Royal Society report, um, which kicked off, um, fairly significant research funding in the UK. Can you describe that? And was that really, am I, am I right to call that kind of the, the switch to sort of the modern era of SRM?

Oliver Morton: Obviously the switch to the modern era of SRM Pete was you taking up the study of the subject. But yeah, I think there’s a lot to be said for that. Uh, but you’ve got to [00:10:00] understand the Royal Society report as being very directly a response to Crutzen and what has happened at the time that Crutzen makes his intervention and the fact that there is now more interest.

And the fact that it was a big report from the Royal Society, again, who the messenger is matters. It was also a very broad ranging report in that it looked at all sorts of consequences, its social and political and economic factors, as well as the, as the physics of both solar and what we would now call carbon geoengineering. So really, in that sense, it really did make a sort of like defining, uh, contribution. I mean the National Academies of Science in America had not done anything similar in the similar sort of time frame. So yes, it really did, uh, kick off a lot of new thinking on the subject. It brought new people into the area. It was, it was a very, very influential thing.

Dr. Pete Irvine: So now let’s turn to, to Bala. Um, your first publication was in the year 2000. Um, what was that paper about and how did it come to be? [00:11:00]

Govindasamy Bala: Yeah. Um, you know, at that time I was working in Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and Ken Caldeira was a colleague sitting next to my office. I mean, Ken actually at that time, you know, showed me the NAS 1991 report, you know, which talks about how to respond to climate change and one chapter actually discussed, you know, various geoengineering options. So he said, okay, nobody has ever really modeled whether these geoengineering options would actually work. The thing that we actually really were interested was basically, if you look at the, um, uh, you know, IR trapping by greenhouse gases, Particularly CO2 and, uh, the solar radiative forcing, both temporally and spatially, you know, they have really very, very different, uh, patterns. You know, for instance, sunlight is mostly in the tropics and, you know, the [00:12:00] polar regions receive very little sunlight. In temporal, for example, you know, there are seasonal changes in, you know, if you particularly look at the high latitudes and mid latitudes, there is very strong seasonal solar forcing, but CO2 doesn’t have that. So we were actually curious, you know, these differences in the pattern of, you know, radiative forcing between the solar and the CO2, um, forcing, uh, can we really offset? I think that was the question we had, you know, you know, obviously. So we actually thought there will be large residual, you know, particularly, uh, uh, seasonal cycle will not be really effectively countered by doing solar geoengineering.

So we wanted to anyway, test this out in a climate model. So I think we started this work, uh, in 1999 and I think anyway, the results are, results were interesting in the sense that we found that the, you know, effects of climate change could be [00:13:00] effectively offset by, um, you know, dimming the sun. Um, I mean, of course there were very little, you know, residual or overcompensating changes in the polar regions and the tropics. But if you look at the overall, uh, you know, CO2 induced climate change, these residual or overcompensated changes were extremely small. That’s where we started our modeling work. And, uh, I think even after that, I remember, uh, we probably wrote a couple of papers immediately after that. Um, because at that time in Livermore Lab, you know, we were actually, there was an initiative to do carbon cycle modeling.

So we actually looked at, um, uh, how solar geoengineering, you know, would actually impact the terrestrial, uh, biosphere. So that paper we got, I mean, we published in another two years, so 2002. Um, we also looked at whether this will really work at higher amounts of CO2. Uh, so that, you know, so we [00:14:00] actually after 2003 or so, um, there was still no, you know, uh, nobody was really talking about it. So after that, I think that we pretty much stopped. I mean, we moved on to do different things, but I remember in 2006, I think, Paul Crutzen’s editorial, came out. I think ever since, uh, that time, I think the field basically took off.

Dr. Pete Irvine: Oh, yeah. I’d like to jump in there. I guess one of the big, um, developments, um, since you got into it was the, uh, start of the Geoengineering Model Intercomparison Project. Um, can you explain what that is and its significance?

Govindasamy Bala: Yeah. Of course, you know, I’m, I’m not directly involved in GeoMIP. So basically, you know, when you get a result using a climate model, one thing we know that is, you know, the, there is a lot of uncertainty. I mean, you can actually classify, let’s say, the uncertainty into three things, the internal variability, model uncertainty, [00:15:00] and scenario uncertainty for the future. So there is this spread in model results. People usually, you know, do the same experiment with the multiple models to understand this spread. This kind of model intercomparison is extremely useful for two things. One is to understand this spread or uncertainty and also to check whether, you know, someone let’s say gets a result like what we did. Is it really robust? You know, for example, let’s say a simple question like, okay, um, global warming will let’s say lead to intensification, intensification of the hydrological cycle. You know, so you want to actually see whether this is true in every climate model. So that is what we really refer to as robust.

So any robustness of this in a model produced result, you can actually get that by doing basically, you know, asking a bunch of modeling groups to perform the same experiment. Today, in fact, [00:16:00] IPCC uses results from this bunch of climate models to basically, you know, project the future, um, and you know, that really nicely quantifies the uncertainty and spread in, uh, our future climate change projections.

So this same idea was actually, you know, basically, uh, adopted for this, uh, GeoMIP. I think the first, uh, GeoMIP, uh, um, experiments were initiated in 2011. Uh, with about, you know, I think, uh, uh, I’m not sure how many models take part today, but I think initially it was about roughly about 10 climate models. GeoMIT basically helps us to understand the robustness of the results, you know, produced by individual climate models, as well as it helps us to identify the spread in model outcomes.

Dr. Pete Irvine: So, turning to Inés now. Another of the big developments in SRM research came with the start of the Degrees Modeling Fund in 2018. Inés, [00:17:00] you first started studying SRM after receiving a grant from Degrees. Could you explain what The Degrees Initiative is and what their modeling fund supported?

Inés Camilloni: Yes, sure. Degrees is a UK based NGO, and Degrees stands for DEveloping country Governance REsearch and Evaluation of SRM. And the main objective of Degrees is to support research for SRM impacts in developing countries through different activities.

The first one is obviously to fund researchers in the Global South, but also to promote different outreach activities through workshops, not only with the participation of researchers of different countries in the Global South, but also with policymakers and journalists, for example. Another important activity of [00:18:00] of degrees is related to networking through, um, collaboration between South and North researchers, but also South, South, uh, researchers.

Dr. Pete Irvine: So, um, what did you find when you did that work on, on impacts in South America? What did you focus on?

Inés Camilloni: The focus of my research was the potential impacts of SRM through stratospheric aerosol injection in, in La Plata Basin. This is a large basin in Southeastern South America. It’s the most populated region in the continent, and also with large, um, mega cities, and it’s really important for many economic activities and water availability in this basin is really relevant.

We know that this region is really impacted through the occurrence of El Niño through flooding [00:19:00] events or La Niña through severe drought events. So for, for me and, and my research group, it was really the focus to, to try to answer the potential impacts of climate change in this region. And when we have the opportunity to, to, uh, have funding from Degrees, uh, our research question was, what would be the, the potential impacts of SRM in, in this basin and, and we wanted to know changes, potential changes in water availability through changes in, in river discharges that the main river discharges we have in the basin. And what we found is that we can expect under an SAI scenario that there would be an increase in precipitation and also an increase in water availability through, uh, increases in the mean discharges of the [00:20:00] main rivers like the Paraná and Uruguay River that we have in the basin.

But we also found that we can expect an increase in the minimum discharges and this was also good news because we can expect to produce more hydroelectric power through having more water available in this river, because we have really huge hydroelectric power plants. But we also found that we can also expect an increase in the maximum discharges.

So under an SRM scenario, we could also expect, uh, an increase in, uh, flooding events. So, uh, what we found is that we can have positive and also negative responses to, to this technology. Obviously, under the, uh, single scenario with the single model we analyzed, but at [00:21:00] at least it was the starting point to, uh, do more research to, to try to answer this, this research question.

Dr. Pete Irvine: Is it safe to say that prior to 2018 that SRM research was mainly dominated by, uh. researchers in the Global North with the exception, notable exception, of Bala here.

Inés Camilloni: Yes, sure. It was absolutely dominated by the Global North. And after Degrees, there was a beginning of research on SRM in Southeast Asia and Africa and also in in Latin America and the Caribbean region. Now through Degrees we have many research groups in these different regions and the Degrees projects also produce, uh, relevant, uh, papers, publications, review publications. Up to now, there are almost [00:22:00] 30, uh, papers showing the different, uh, impacts that we can expect in these different regions and of SRM, mainly in the form of stratospheric aerosol injection.

Dr. Pete Irvine: Great. Well, sticking with an international theme, um, the Convention on Biological Diversity, or the CBD, uh, reached a decision on SRM in 2010. Uh, the first time it was addressed in an intergovernmental setting, I believe. Um, Cynthia, what did the CBD decide and what was its significance?

Cynthia Scharf: Yeah, the CBD took up this issue in 2010, and what they were looking at is the responsible or hoped to be responsible use of research in, um, in, as it affects biodiversity. And so the decision, it was a decision, not a de facto moratorium, was non-binding, meaning it was not legally enforceable. But it served more as guidance to members of the the convention, [00:23:00] meaning governments on what might be responsible research that could be permitted and what should not be permitted. Um, the decision, as I said, is often referred to as a de facto moratorium. Um, first of all, just from a clarification point of view, the United States is not a member of the CBD and so the effect of having a moratorium without such a large international power, uh, adherent to it is very limited. But nonetheless, it had an important symbolic effect and it is often referenced by NGOs today who are interested in looking at SRM and, and very cautious and I would say very strongly on the side of looking at the precautionary approach towards research.

Dr. Pete Irvine: Have any other international fora taken up this issue since CBD did in 2010?

Cynthia Scharf: There have been bits and pieces in, in other [00:24:00] parts of international governance. So, for example, in the Montreal Protocol last year, there was some important information about potential effects of SRM. Um, there are also bits and bobs in the London Convention, The London Protocol concerning oceans, um, but the one glaring absence in terms of international governance has been the international climate negotiations under the UNFCCC. There have been some informal discussions among countries, uh, among potential negotiators. about SRM just in the last maybe year or two, but thus far the UNFCCC has not touched it.

Dr. Pete Irvine: So it sounds like this hasn’t really been picked up very much in international fora. Is it really on the radar of policymakers? Are they, is this going on mainly behind closed doors or is it just not really being talked about?

Cynthia Scharf: I was with the Carnegie C2G Initiative when it [00:25:00] started in 2017 and we spent seven years talking to policymakers around the world, um, in private meetings, sometimes in public events, public conferences, but mostly behind closed doors, trying to raise awareness of what SRM is and what it isn’t. And when we started, there was really a sense of incredulity that we’re even raising this topic. Why are we talking about this? It seems almost like science fiction.

Um, and I think our interlocutors tolerated us just because we had a background from the UN and we had done work on the Paris Agreement. Over the course of that seven years, the, the arc of that conversation did change. Um, particularly so I would say in the last two years, um, post pandemic. And I say that for the reason that the pandemic really had a mental shift, I think for all of [00:26:00] us, but when I’m speaking about this in the context of SRM, I’m speaking about the fact that some global, uh, perhaps black swan event could actually happen and that we needed to look at proactive anticipatory governance and some precautionary approaches so that if and when these black swan events happened, that the world was better prepared.

And so the conversations we had, um, with policy makers, and these were with, governments, um, over 60 national governments, including many of the climate vulnerable countries, the least developed countries, the Pacific islands, um, as well as the large economies. And also, with senior leaders in all of the respective UN bodies, UN entities that work on climate. That conversation shifted from one of kind of, as I said, incredulity to [00:27:00] anxiety. Anxiety and interest. And of course what fueled that, in addition to this recognition of, of global fragility, was the worsening climate and really falling behind with the Paris pledges, we hoped that we might accomplish by, by this time. And the anxiety arises from a sense of, wow, what if this new method or technology would deter or slow the political momentum we need to actually do what the Paris Agreement tells us we must do? And they call that moral hazard in, in an academic sense, and I can verify that it is real among the governments and policymakers who are looking at this issue.

They know just how difficult it has been to get political momentum behind what we see in the Paris Agreement. It took, [00:28:00] effectively, decades to get where we were in 2015 at COP21. And no one who has worked on that agreement and, and trod that road for so long wants to see a diminution of political momentum behind that.

Um, as I said, SRM is, uh, it’s of course not a solution. It is not a substitute for reducing emissions drastically and urgently and for scaling up adaptation. But the fear is it could take the pressure off and it might divert the public’s attention into something that would lull them into a sense of relief or a sense of, don’t worry, we’ve got this. Um, and certainly policymakers do not want to encourage that.

Dr. Pete Irvine: That was a bit of a whistle stop tour of the history of SRM, um, that took us up to about 2020. So I just want to briefly review some recent developments and then look ahead a little. Um, so, [00:29:00] Ollie, the funding for SRM research had been quite patchy, I think, from 2009 to 2020, with like, you know, efforts popping up in the UK, USA, Germany, China, then falling away again. Um, how have things changed in recent years?

Oliver Morton: Well, I think it’s very important here to look at things in comparison with the other form of geoengineering, carbon dioxide removal. That had the sort of moment that Cynthia was talking about in 2018 when the IPCC’s special report on 1.5 made it clear to people in a way that they hadn’t seen before, how much carbon dioxide removal was now getting baked into the scenarios people were talking about. And there was a big rush at that point to put money, both private and public money, into CDR because people suddenly saw how much it was being relied on.

And the sort of moral arguments that Cynthia was talking about just then, they apply very much to CDR too. If you put effort into CDR, people think that you’re [00:30:00] reducing your effort on straightforward emissions reduction. So it seems like we’ve had a worked out version of the sort of thing that can happen with CDR and we’re now wondering whether that’s going to happen with solar geoengineering. We are seeing more money coming into the space. Um, the group that I’m associated with as a trustee that funded some of Ines’s work, Degrees, we are seeing more money, we’re finding it easier to raise money, somewhat at the moment, that doesn’t mean people shouldn’t keep giving to us. We want more money, and you’re seeing other groups, other groups getting into this sort of space fairly successfully, other NGOs and things.

What we’re lacking is serious government commitment to trying to find out what is going on, what could go on, what might go wrong, what might be needed. That sort of serious look at things by governments, ideally inter-governmentally, that’s [00:31:00] still not happening. And so, although there’s more money, largely from very rich individuals and that is frankly welcome because it is, it allows us to do stuff, it also produces a perception of the schemes as techno fixes rather than as part of a real discussion about what to do in a world that overshoots the Paris pledges that Cynthia was talking about.

Cynthia Scharf: If I may add on to what Ollie just mentioned, in the last two or three years, um, we have seen that the conversations around climate tipping points have garnered more attention, um, and there is a sense that potentially SAI, one form of SRM, might be helpful in slowing or averting one of those climate tipping points, one or more.

Um, I was just in the Arctic two weeks ago, I was at the Arctic Circle Assembly in Iceland, and there was definite, um, anxiety [00:32:00] and attention paid to the precarious situation in the Arctic, which is melting four times faster than anywhere else in the world. Um, and there’s concern that not only of sea ice loss and melt of Greenland’s glaciers, but also something called the AMOC, the Atlantic Meridional Ocean Current, might slow down or perhaps even collapse.

Um, and so the question of are there methods that scientists might be able to, to bring to the table that look at these things, previously, that kind of discussion was not taken seriously. I think we are about to see a change in that conversation toward greater interest in serious research about what might happen, what might be potential risks, what might be potential benefits, and this large pool of uncertainties that [00:33:00] governments are focused on.

I might also add that in 2023 two events took place within a week of each other. Um, the European Union, uh, issued a report on security and climate change, and in that report, there were a few paragraphs directed at SRM. And specifically, the EU was flagging its concern about research in SRM and wanting to know more. Wanting to know more about the risks as well as the uncertainties and it’s interesting to note that there wasn’t any reference to potential benefits of SRM. It was really seen through a precautionary approach. Let’s look at what we don’t know, let’s do research to look at those potential risks. But significantly, the EU also said it would support and promote international talks on how [00:34:00] SRM might be governed. And this is one of the first times that a group of governments has stated in writing publicly that it will support and promote this idea of international talks. It did not say which venue, which kind of UN process that this might take place. Um, and there is no one ideal UN process or entity where this conversation should take place. Um, as mentioned, the CBD has looked at this, The London Protocol, The London Convention, um, The Montreal protocol, but there is no one natural home for this discussion.

Just one week after the EU’s report, The White House issued a report, which it stated very clearly was mandated by the U. S. Congress, that was stamped across the front cover and I think on every page, um, to look at what kinds of research would be needed on SRM and what are [00:35:00] some of the questions and where might this go. But specifically, it did not call for talks, international talks, on the governance of SRM. It was much in favor of international collaboration on research, international, um, interdisciplinary collaboration, but the issue of how might this be governed was really not taken up in an international sense. Um, so those events plus the growing attention to climate tipping points are important pieces of this, but I also want to flag one other element, and that is social tipping points.

What I mean by that is a situation in which the climate has become so lethal, so dangerous to human health or human well being, that large parts of society are basically saying to governments, do something. And in [00:36:00] those moments, there could be a tipping point generated by society that leads a government or group of governments to say, maybe we should look at this thing called SRM because it is the quickest response that would generate impacts that the public might actually tangibly feel.

It’s the quickest option we know for anything this century that might change the climate in a perceptible fashion. It’s significantly less expensive than decarbonizing the global economy. And at the moment, there are no binding. comprehensive international governance around these technologies. For those three reasons, it might prove tempting for a government or a group of governments or some other entity to look at SRM. So I think it’s important to look at both the climate as well as the potential social [00:37:00] tipping points around this.

Dr. Pete Irvine: So, Inés, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which has a really important place in international policymaking on climate change in terms of informing it, particularly for the developing world, um, that’s only devoted a limited number of pages in the past to SRM, uh, but a new report is being planned. Um, can we expect this next report to have much more on SRM?

Inés Camilloni: I don’t really know the way where SRM will be taken into account in the 7th assessment report of the IPCC, but the good news is that for the call of nominations of experts to participate in the scoping meeting of the 7th assessment report, one of the topics was solar radiation modification. There was a clear call for experts on, on the basis, not only on the physical science, but also on the social science and scenario, because it’s a cross [00:38:00] working, uh, issue to, to be addressed by IPCC.

Dr. Pete Irvine: So since your first paper in 2000, Bala, there’ve now been hundreds of, of studies, um, cloud modeling studies of SRM, uh, broadly finding similar things to what you found. Um, but in recent years, we’ve seen the first SRM field experiments where researchers are going outside to release materials, uh, to try and understand how it would affect the climate. What are your thoughts on these developments and how important are they?

Govindasamy Bala: Yeah. You know, I mean, I would like to see a published journal paper on that. Um, you know, I mean, I think what, uh, what we keep hearing is, you know, these experiments are planned and advertised and the public is, you know, informed about when it’s going to happen, et cetera, et cetera. But, um, I am actually really [00:39:00] surprised, uh, about, what happened with, the SCoPEx experiment by the Harvard team and, um, also the, another marine cloud brightening experiment in California that also got canceled.

Um, the, I think the Great Barrier Reef, that was a MCB experiment and, um, you know, it was, um, it’s not really clear. I think, you know, it was really wrapped under this, uh, coral reef restoration project. You know, the main focus of that, you know, project was really, you know, saving the corals and, um, the MCB experiment was really a component of that coral reef restoration.

Um, I still think, you know, there is, uh, resistance to this and partly because of the lack of, uh, governance, I believe. [00:40:00] I think, you know, there is no governance structure, uh, right now. Um, so, uh, you know, I would like to really, you know, see an experiment and, uh, a publication about that. You know, even today there are a lot of, lots and lots of experiments, uh, field experiments on aerosol cloud interaction.

Uh, nobody probably worries about it, but the moment you actually say this is basically a geoengineering experiment, I think still there is some kind of, you know, maybe I don’t know whether I can use the word taboo for this. Uh, you know, geoengineering was a taboo 20 years back, and, uh, I think now probably in terms of modeling, I think it’s no more a taboo, but I think still for field experiment, my sense is, um, It’s a little taboo.

Cynthia Scharf: If I may, I, I completely agree with Bala. Um, I think there’s something about outdoor testing that has a symbolic resonance [00:41:00] with, with people. Um, regardless of how much potential environmental, um, harm there may be, it doesn’t seem to matter. It’s the fact that it somehow becomes real by being tested outside.

And it, it really, um, piques people’s both, curiosity, and I think galvanizes some of their fears. Um, so in terms of, of the governance, um, governance of research that takes place, uh, in modeling and in the lab, um, following basic academic principles of responsible research doesn’t seem to be contentious, but when moving that research outside, that becomes a different arena altogether, and then deployment of course is even one step beyond that, um, that raises huge questions.

And I like to underscore again, that there really is no institutional home at this point for this conversation for a comprehensive governance framework on this issue and that [00:42:00] if a crisis were to emerge that maybe the best we could do is muddle through, and by that I mean, um, some emergency kind of coordination, um, at the level of perhaps the UN Secretary General, um, trying to cobble together where different parts of the UN system have expertise and, and authority.

Others have, have posited that perhaps we need an entirely new institution to govern SRM effectively. However, just a quick look at the news any day in the last two years or three years will tell you that the appetite for multilateralism is definitely on the down, and I just don’t see the political momentum and leadership you would need to create an entirely new international entity to govern SRM. So for the moment, um, we’re stuck with the muddle through and coordinate what we can model.

Dr. Pete Irvine: Well, I’d like to thank all my guests, Cynthia [00:43:00] Scharf, Inés Camilloni, Govindasamy Bala, and Oliver Morton for taking us through the history of SRM and for reflecting on where we are at the moment. Thanks for joining.

Thanks for joining us for our first episode of the Climate Reflections News Roundup. If you like this episode, please rate and review us wherever you got this podcast. The Climate Reflections Podcast is a production of SRM360, a non-profit knowledge hub supporting an informed, evidence based discussion of sunlight reflection methods.

To learn more about SRM or to ask us a question, visit srm360.org.